.png) In 1974 I finished and produced copies of my ‘Fort Pitt. Some notes on the History of a Napoleonic Fort, Military Hospital and Technical School' using the school’s gestetner machine. (link) (link) Then the Divisional Education Officer, Mr Dean, who had offices in Fort Pitt House and had a great interest in the history of the School, had my ‘History’ published in booklet form by the Kent County Library.

In 1974 I finished and produced copies of my ‘Fort Pitt. Some notes on the History of a Napoleonic Fort, Military Hospital and Technical School' using the school’s gestetner machine. (link) (link) Then the Divisional Education Officer, Mr Dean, who had offices in Fort Pitt House and had a great interest in the history of the School, had my ‘History’ published in booklet form by the Kent County Library. Today, all of the Fort’s surface buildings have been demolished and its defensive ditch has been levelled. Ironically, the most substantial remains of Fort Pitt, its magazines, remain unseen, Grade II listed, below ground and sealed off.

* * * * * * * * *

There was certainly some kind of farming settlement on the site of Fort Pitt before and during the Roman occupation, with finds of pottery in 1932, as well as human remains and that of pig, horse and long-faced Romano-British ox, but there was no fortification. The walled Roman town of Durobrivae, which guarded the bridge crossing the River Medway, was only a mile away and would have provided a ready market for any farm produce. It is probably safe to assume that the farming settlement continued after the Romans withdrew and after the storming of Rochester by, the first of the Jutish kings of Kent, in 455 AD and during the later Danish invasions in the tenth century and then continuously until the 18th century.

The strategic importance of the hilltop on which Fort Pitt was built rested on the fact that it offered a first class view of the River Medway and Chatham Dockyard which, when it began to increase in importance, so too did its importance as a target for England’s European enemies and colonial rivals, France and the Netherlands This was clearly shown in the summer of 1667, when the Dutch fleet, under Admiral de Ruyter, sailed up the Medway and burnt ships in the largely undefended Dockyard.

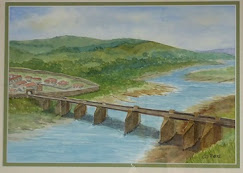

.jpg) Nothing happened for 13 years then, with the outbreak of war with the new French Republic in 1793 and the following rise of Napoleon, Government orders were issued for the construction of a fort to be called ‘Pitt’ after the wartime Prime Minister, William Pitt. Along with its sister fort, Clarence, and two outlying towers, Delce and Gibraltar, which controlled road access to Rochester Bridge, it would finally provide a formidable landward defence of the Dockyard as illustrated in the view from Fort Pitt in this engraving dated 1829. In action, the Fort’s fire would have crossed with that of Fort Amherst, on the opposing north-eastern high ground above Chatham, which had been fortified as a major citadel. (link)

Nothing happened for 13 years then, with the outbreak of war with the new French Republic in 1793 and the following rise of Napoleon, Government orders were issued for the construction of a fort to be called ‘Pitt’ after the wartime Prime Minister, William Pitt. Along with its sister fort, Clarence, and two outlying towers, Delce and Gibraltar, which controlled road access to Rochester Bridge, it would finally provide a formidable landward defence of the Dockyard as illustrated in the view from Fort Pitt in this engraving dated 1829. In action, the Fort’s fire would have crossed with that of Fort Amherst, on the opposing north-eastern high ground above Chatham, which had been fortified as a major citadel. (link)

![]() Construction of the brick and earth fort began in 1805 with an expenditure in that year of £22,000, rising to a total of £69,000 by completion in 1813. Doubtless, part of the cost was due to pilfering. The Edwardian Antiquarian Edwin Harris recorded that cartloads of bricks were brought up one side of the hill and then taken secretly down the other side and sold for private gain.

Construction of the brick and earth fort began in 1805 with an expenditure in that year of £22,000, rising to a total of £69,000 by completion in 1813. Doubtless, part of the cost was due to pilfering. The Edwardian Antiquarian Edwin Harris recorded that cartloads of bricks were brought up one side of the hill and then taken secretly down the other side and sold for private gain.

The Fort was completely surrounded by a defensive ditch, with brick-lined scarp and counter scarp walls, to a depth between 15 – 20 feet and a projection of iron spikes, known as a ‘chevaux de fries’, built at the top of the scarp walls to thwart the enemy scaling them if they had entered the ditch. The one shown here was not at Fort Pitt. Above this was a sloping terrace which rose another 19 feet and was surmounted by a fire- step which ran around the inside of the perimeter of the Fort and provided cover for its musket-firing defenders.

.png)

A massive engineering undertaking, the Fort’s four, corner bastions symbolised old-fashioned ideas in fort defence, yet its forward blockhouse, central tower, defensive ditch, underground chambers and ‘v’ shaped ravelin at the rear of the fort, were all new and experimental.

.png) Two sections of the outer, counterscarp wall remain today and stand to the east (left) and west of what was the University for Creative Arts and now closed down, in the gap created after the blockhouse at the front of the Fort was demolished in 1932. A drawbridge, complete with defensive guardhouse, gave access to the Fort and crossed the ditch to the east of the blockhouse and was located roughly in the position of the main entrance to Fort Pitt Grammar School today.

Two sections of the outer, counterscarp wall remain today and stand to the east (left) and west of what was the University for Creative Arts and now closed down, in the gap created after the blockhouse at the front of the Fort was demolished in 1932. A drawbridge, complete with defensive guardhouse, gave access to the Fort and crossed the ditch to the east of the blockhouse and was located roughly in the position of the main entrance to Fort Pitt Grammar School today.

.png)

‘“You know Fort Pitt?” “Yes; I saw it yesterday”. “If you will take the trouble to turn into the field which borders the trench, take the foot-path to the left when you arrive at an angle of the fortification, and keep straight on, till you see me, I will precede you to a secluded place, where the affair can be conducted without fear of interruption”.

"The evening grew more dull every moment and a melancholy wind sounded through the deserted fields, like a distant giant whistling to his house dog. The sadness of the scene imparted a sombre tinge to the feelings of Mr Winkle. He started as they passed the angle of the trench – it looked like a colossal grave’ .

In addition to the ditch, the fort was further strengthened by four corner bastions which had cross-fire with each other and gave a line of sight to any attackers in the ditch.

.png)

.png) A small casemate, built into the trench wall on the western counterscarp of the ditch, was a gallery with gun loops from which troops from the defending garrison could fire on an enemy attempting to access the ditch on the western side of the blockhouse. This particular casemate had a sentry box with a door and window on the outside with two gun loop holes, marked ‘X’, on the inside, which could be used if the enemy stormed the box. Ingeniously, the casemate was connected to the blockhouse by means of a tunnel, complete with air vent. There were many such casemates built at strategic points into the walls of Fort Pitt. The drawbridge complete with guard house provided access the Fort crossed the defensive ditch to the east of the blockhouse and was located roughly in the position of the main entrance to Fort Pitt Grammar School today.

A small casemate, built into the trench wall on the western counterscarp of the ditch, was a gallery with gun loops from which troops from the defending garrison could fire on an enemy attempting to access the ditch on the western side of the blockhouse. This particular casemate had a sentry box with a door and window on the outside with two gun loop holes, marked ‘X’, on the inside, which could be used if the enemy stormed the box. Ingeniously, the casemate was connected to the blockhouse by means of a tunnel, complete with air vent. There were many such casemates built at strategic points into the walls of Fort Pitt. The drawbridge complete with guard house provided access the Fort crossed the defensive ditch to the east of the blockhouse and was located roughly in the position of the main entrance to Fort Pitt Grammar School today.

.jpg)

The Fort’s firepower consisted of ten 18-pound cannon, ten 18- pound carronades and four 10-pound mortars.

The munitions which fed the guns in the block house were stored in underground magazine chambers constructed behind the blockhouse. Accessed by three main entrances, the two. side-by-side chambers which made up the central magazine were domed in shape. The bricks in the walls of the chambers were interspersed with wooden blocks which would act as shock absorbers in the event of an explosion, thus diminishing the force of the blast. (link) (link)

A protective semi-circular tunnel was wrapped around the central magazine with the propose of absorbing the force of the blast in the event of an explosion. In addition all the floors were covered with leather to prevent accidental sparks from the soldiers' boots causing an accidental ignition of the explosives stored in the magazine.

.png)

In 2011, for the first time since the 1940s, the chambers were entered through an entrance which had once been a gun port overlooking the Dockyard. The opening was carried out in a combined operation between the Kent Underground Research Group and Fort Amherst and was based on information supplied an 82 year old Medway resident who had been a pupil at the Day Technical School for Girls on the site during the Second World War, when the tunnels were used as air raid shelters for the School. (link) Once the researchers had carried out their investigation, the tunnels were resealed.(link)

The only building above ground level was the central Tower. It was completed in 1808 and was protected by two long guns at the front and two cannonades at the rear. It ran up on three storeys and housed the Fort’s well, 116 feet deep and accessed on the ground floor. The Tower provided a platform for the Fort’s communication with its sister Fort, Clarence, the Amherst Redoubt and the Delce and Gibraltar Towers. The English Heritage Report on Fort Pitt described it as : 'A substantial three story keep with corner turrets to a flat roof'. (link)

There was a further complex of underground chambers to the east of the magazines. One of these chambers consisted of a 20 foot square reservoir, lined with a brick wall, 2 feet thick and insulated against leaks with 2 feet layer of clay and finally 9 inches of brick. The water was impure and when pumped to the surface was used for washing and not drinking, with its overflow channeled into the surrounding ditch. It was uncovered, perfectly preserved 150 years later, when building excavations were made by the School on the site in the 1960s. Its existence may explain why a 3 horse, powered water pump was recorded on the site at the time of the later Hospital.

The ‘experimental’ ravelin was a defended outwork at the rear of the fort and was reached by a covered passage or ‘carponier’ built across the defensive ditch. Two experimental ‘cavaliers’ or raised mounds gave additional height for the defenders along this stretch of the ditch and with those on the ravelin, who would attempt to thwart an expected encircling attack on the Fort. Fort Pitt’s use as a functioning fort was remarkably short-lived and in 1814 it assumed its next role which I shall deal with in Chapter Two : The Army Hospital’.

John Cooper

Linked later or earlier chapters :

Chapter One : Construction and function as a Napoleonic Fort

Chapter Two : The Army Hospital

Chapter Three : The Army Hospital and Medical Research

Chapter Four : The Army Hospital in the Crimean War and Queen Victoria's three visits

Chapter Five : Florence Nightingale and the Army Medical School

Chapter Six : The New Hospital Wing and the First World War and the visit of the King and Queen

Chapter Seven : Conversion of the Fort into the Medway Technical High School for Girls

Chapter Eight : The School in the Second World War and the second half of the Twentieth Century

Chapter Nine : The Site of Fort Pitt in the 21st century.

See also :

Fort Clarence in War and in Peace

The remarkable History of Fort Clarence in the City of Rochester and County of Kent (link)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment