The genesis of the secondary school for girls which would and still does occupy the site of Fort Pitt began during the First World War when the Army Pay Corps badly need clerical workers and to ease this shortage, the Chatham Institute began training 51 local girls for this purpose in 1916. Two years later the nascent school moved from the 'Technical Institute' to Elm House, beneath Fort Pitt on the New Road. By 1919 it was known as ‘The Junior Commercial School’ and by 1920 it was teaching over 130 pupils. The School’s curriculum was widened to include needlework and millenary subjects as well as commercial ones associated with book keeping and in 1923 it changed its name to ‘The Commercial and Trades School’. Its pupils were aged 14-16 and followed a two year course working a 30 hour week and a 9 period day with 9 weeks holiday a year. In 1926 the Medway Board of Education made the decision to turn the Trades School into the first ‘Day Technical School for Girls’ in Britain. With Miss Moffat as its Head Teacher, the school was still an unsatisfactory, makeshift affair, with classes being held in the 3 rooms on the top floor of Elm House, a building the School shared with the local Education Office. In addition, classes were also held in Navy House and the Technical Institute with outside games held at the new home for the Technical School for Boys at Holcombe Manor and indoor ones in the Drill Hall, with pupils meeting in a building called ‘The Hut’ for lunch.

By 1927, the search for a home for the school was becoming more urgent because courses had been extended to 3 years and the school roll increased to 270. Twelve year old Rose Sears, who joined the School in 1926, was reported in the local newspaper as saying : ‘I was one of a batch of about fifty girls who joined the School in the Summer Term 1926. We had to use four or five rooms, including the gym at the Boys’ School in the High Street and four class rooms in Elm House on the New Road. This had a large lawn surrounded by trees and it also housed the Medway Education Board Room and Office, we were expected to be on our best behaviour there. Miss Moffat set about building a community and instilling in us that unknown word, ‘tradition’, in a very enthusiastic way. We had one afternoon when we crammed into the ‘hall’ at the Tech. and sang. How I enjoyed that!’.

.jpg)

Sports Day was held on the field at Holcombe with the one held in 1926 involved races with potatoes, egg and spoon, slow bicycles and sacks. In the conventional races there was no stop watch and although points were given, the times were not recorded. The institution of a Sports Day indicated that, despite the problems of accommodation, Miss Moffat and her staff were determined to lay down traditions and build for the future and at the first Speech Day held in Chatham Town Hall in 1927, school trophies – the Whyman and Twigg Cups were presented by Lady Alexander Sinclair who also presented a trophy of her own for and essay on ‘Naval Tradition’. In addition, the Chairman of Education Committee presented the School with a ‘Tradition Chest’ which in time became known as the ‘Archives Chest’.

Miss Moffat’s Report on Speech Day in the Central Hall in March 1929 revealed the type of jobs the girls were taking after leaving school. She said that she was glad to see that “They made good in such positions as improvers, designers, first hands in London fashion houses like Reville’s, Bradley, Worth and Jays, children’s’ nurses, sewing maids and lady’s maids, hospital and mental hospital nurses, advertising artist and journalists’ assistants, saleswomen, hotel assistants and reception clerks, band and solicitors’ clerks, auctioneers, estate agents and insurance clerks, shorthand typists, cashiers and book keepers, writing assistants in H.M. Dockyard and various Government Offices, telephonists, telegraphists and sorting assistant”.

It was an impressive list and no doubt spurred the Education Board to find new premises for their new and promising Technical School for Girls which Miss Moffat said, was "The only school of its kind in England and was the most difficult, for no other school carried on in three overcrowded buildings nearly a mile apart".

.png)

More pressure came from the Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education, the Duchess of Atholl, who was the guest speaker at the Speech Day, the local newspaper reported :

The Duchess had the distinction of being, from1924 to 1929, the first woman to serve in a British Conservative government and the first woman elected to represent a Scottish seat at Westminster.

The accommodation problem was finally solved when the Education Board agreed to buy site of Fort Pitt with its attendant buildings and the outlying Fort Pitt House for the sum of £6,000. St. Bartholomew’s Hospital had been given first offer of the site, but had declined. In the event, the takeover of Fort Pitt had been a hasty affair. The Hospital had lain empty for seven years and the caretaker and his staff set about cleaning the place up for when the pupils returned from their summer holidays in September 1929 and the contract for any structural work was given to Vincents of Gillingham.

The first building to greet the new pupils into the grounds of their new school was the guardhouse of the Fort which, dating from 1810, remained in tact, with its musket loops facing the enemy at the front.

.png) The site itself consisted of a collection of disparate buildings which would either be converted or, as in the case of the mortuary, demolished. There were five separate ward blocks and an operating theatre and and administration block and individual buildings which had served as :

The site itself consisted of a collection of disparate buildings which would either be converted or, as in the case of the mortuary, demolished. There were five separate ward blocks and an operating theatre and and administration block and individual buildings which had served as :The ophthalmic and dental blocks

The store room

The dining room

Accommodation for the nursing sisters

Accommodation for medical officers

The pay office

Inside the school itself the conversion of the rooms in the Hospital’s Administrative Block had been fairly straightforward. On arrival at the school the pupils would enter through the front doors and passed in sequence on the left :

* the telephone room which had been the hospital telephone room

* the Headmistresses Outer Office, once the Senior Medical Officer’s Outer Office

* the Head’s Office, once the Chief Clerk’s Office

* and then past a Stock Cupboard, once the Receiving Room

* next to the Sick Room, once the Dispensary with its hatch

On the opposite side of the corridor was in sequence :

* the School Office, once the Clerk’s Office

* a spare room, once the Quarter Master Sergeant’s Office

* Store 10, once the room for surgical appliances and drugstore

* and past the electric lift in the stairwell and a room for the P.E. Staff room with ease of access to the gym once the room for live animal stock kept in proximity to the hospital kitchen and ready for slaughter and cooking.

Doris Ripley, a pupil at the School from 1928-31 recalled her first day at Fort Pitt : ‘I well remember the excitement of coming into the empty building and quiet getting lost in the corridors. The grounds were very rough and were surrounded by a dry moat which was immediately ‘out of bounds’ so there was little space for play. I also remember the lorry carrying all the chairs from Elm House up the hill and which we helped unload to take them into the building’.

On the ground floor to the rear of the Hospital Administration Block the Hospital Kitchen became the School Kitchen with food transported to the first floor by means of the electric lift. A pupil recalled : “Trestle tables were put up along the top corridor (right), each morning about 11 a.m. and taken down at 2.30pm. All these and the top hall were filled with two shifts for lunch”.

If Doris was called to the Staff Room she would climb the main staircase and walk to the front of the building past the room with staff noticeboards once the Massage Room to the Main Staff Room once the Orderly Medical Officer’s Room. Close by was the Staff Library, once the X-ray Room and Developing Room. Also in this area, the Matron’s Office had once been the Hospital’s Committee Room and next door the sick room had been the Sister’s Room. The Staff Canteen had once been a room with a portable bath. At the top of the stairs on the right, the room which had once housed the electric motor to power the lift in the stair well, was later converted into the career’s room.

.png)

.png) On the first floor of what had been the 1910 Hospital block the ward, had been converted into a room where Doris might have perfected her needlework and dressmaking. One pupil recalled : “I used to love the needlework room above the hall as it was so long and roomy”. For Art, the operating theatre attached to the block had been converted and her work would have been lit from above by the skylight in its ceiling.

On the first floor of what had been the 1910 Hospital block the ward, had been converted into a room where Doris might have perfected her needlework and dressmaking. One pupil recalled : “I used to love the needlework room above the hall as it was so long and roomy”. For Art, the operating theatre attached to the block had been converted and her work would have been lit from above by the skylight in its ceiling.

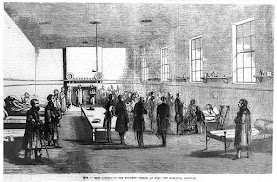

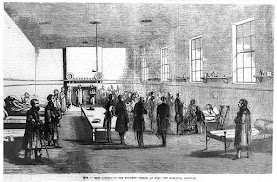

If Doris had followed a commercial course of study with its attendant shorthand and typing, she would have been taught in the old Hospital block in a ground floor classroom, once a ward where Queen Victoria had visited the Crimean War veterans 70 years before. This building would receive Grade II listing in 1950.

If Doris had followed a commercial course of study with its attendant shorthand and typing, she would have been taught in the old Hospital block in a ground floor classroom, once a ward where Queen Victoria had visited the Crimean War veterans 70 years before. This building would receive Grade II listing in 1950.

At this stage, the site, with its blockhouse and deep surrounding ditches intact, was a potentially dangerous environment for school children. When the School took occupancy, only one building, the mortuary, which stood next to the main entrance onto the site had been demolished, much to the relief of one teacher, who when visiting the empty hospital before the Army had left was told by an incumbent : “And this is the mortuary. Mortuaries come in very handy in schools you know. Once, in my school, a boy was killed and we did not have a mortuary to put him in”.

By the time Doris moved into Fort Pitt, it had over 300 pupils and 18 members of staff. Its aim was to give her a progressive course in general education, together with a distinctive vocational education in the later stages. When her application for a place at the School was submitted she was over 12, but below 13 and had to pass the Entrance and Special Place Examinations to get in and her parents agreed to pay the £6 annual fee with the proviso that fees were waived if they couldn’t afford the charge had gained a ‘special place’. Once at school a School dinner was provided at six pence each and if she brought their own food she was charged a small table fee. In the early days of the School, if she had no bathroom at home, she could take advantage of the hot water and still installed hospital baths.

If Doris had followed the Household Science Course, it had been designed for those entering the : ‘Nursing profession and various catering and allied trades, as well as those who intend to be proficient homemakers’. In addition, the French Course was planned to help pupils with the : ‘Vocabulary required in workrooms, showrooms etc. and pupils were taught to read French fashion journals’. To supplement her studies she was expected to do one and a half hours homework each night and parents were required to provide a note if it wasn’t completed.

In 1933 Domestic Science was added to the curriculum. One pupil recalled that : “When Miss Moffat spoke to us about the new course she pointed out that when times were hard a company could manage without a shorthand typist, but everyone had to eat and there were a great many jobs available in the food industry”. It is doubtful thar the pupils studying the subject were told that their lessons were held in the detached building which had once been the section of the hospital which housed the soldiers suffering from mental illness and known as the Asylum. Apparently in the 1930s : “Upstairs several rooms had been equipped as a small flat and it was part of the training to learn to care for it as if it were our own. Downstairs we had a variety of ovens and laundry equipment”. It is one of the buildings on the site listed by National Heritage, in this case as a Grade II in 1974 and therefore defined as a building or structure that is "of special interest, warranting every effort to preserve it".

It is also unlikely that the pupils knew that Councillor Hitchins, the Chairman of the Education Committee, had played an important role in the School’s acquisition of Fort Pitt, when they were photographed in the grounds with him. Judging by the length of the grass this, was not long after the move to Fort Pitt.

A new school badge was designed to fit the School's new home at Fort Pitt. It took the Kent Invicta horse from the old badge and placed it at a centre of a book representing the school’s educational role. The cross was a reference to the site’s history as a military hospital and the crenelated battlements, which the fort never had, but was perhaps a nod to the notion of its time as a Napoleonic Fort. The heavy blue surround represented the River Medway which dominated the view of Chatham and Rochester from the School looking north.

.jpg)

With its own playing field, pupils no longer had to trek to the Boys Technical School at Holcombe and could enjoy sport on their own school site. Here, Sports Day in 1933 had featured a chariot race, perhaps inspired by the 1925 film version of Ben Hur? (link)

With its own playing field, pupils no longer had to trek to the Boys Technical School at Holcombe and could enjoy sport on their own school site. Here, Sports Day in 1933 had featured a chariot race, perhaps inspired by the 1925 film version of Ben Hur? (link)

.png)

The following year the Blockhouse at the front of the school site, which had dominated the Chatham landscape for over a hundred years was demolished, leaving an open area to the front of the school site. Pupil Doris Ripley recalled that previously : ‘On fine days we had team games and physical jerks on a concrete area of land just outside the Fort’. Doris may well have been referring to the the area once occupied by the blockhouse which had been concreted over and on which the Medway College of Art would be built later in the century.

The demolition plan drawn up in the Kent County Council Architect Office in 1932 carried the instruction :

TAKE DOWN THE CASEMATES. RAKE OFF THE WALLS TO EXISTING FOSSEE LEVELS. TAKE DOWN BACK AND INTERNAL WALLS TO YARD LEVEL. CLEAR AWAY ALL FLOORS. (The 'fosse' referred to was the base of the defensive ditch at the front and the sides of the blockhouse.)

In 1936, the School’s first Head Teacher, Miss Moffat, retired after having served as one year as the Principal of the ‘Trades School’ and then as Headmistress of the Technical School. Both she and her staff had worked hard to enlarge the number of subjects taken and broaden the curriculum beyond its exclusively commercial base and the School, for example, was the first in Kent to teach French by speech alone and school visits were arranged to France.

Miss Moffat was clearly a firm disciplinarian who was imaginative in her use of the electric lift which had once lifted patients from the ground to first floor in the Hospital’s Administration Block. Pupil Joan Haigh recalled : ‘Miss Moffat was a very capable Head Mistress, certainly she was very capable of inspiring feat in must if us as well as being able to reduce to tears the hardiest of wrongdoers. The worst punishment possible was to be made to sit on a chair in the lift, which was like and ironwork cage, leaving the naughty one on view to the whole school as they passed up and down the stairs to and from classes’.

In the summer the grounds of the School were used for performing art activity. One ex-pupil recalled : “My memories of school days then were Grecian dancing in our various pretty coloured tunics up on the grass battlements”. She was, no doubt referring to the two defensive ‘cavalier’ mounds of the old Fort, on the south flank of the site where Crimean War veterans had been drawn up ready to be inspected by Queen Victoria 75 years before. One of the two mounds can be seen to the left of the pupils and the soldiers in both photos.

.png)

It was probably Miss Moffat’s idea to have a ‘lamp of honour’, a red electric light in the shape of a flame which stood on the tradition chest in the front entrance of the School, which was turned off when pupils had acted dishonourably. One pupil recalled : “I never forget the day we found the ‘Lamp of Honour’ turned off. At assembly, Miss Moffat walked up onto the platform with her gown flowing from her shoulders. We could tell by her walk that she was annoyed.’ It appears that there had been a complaint about the ‘unruly’ behaviour of the girls who travelled by train from Gillingham to Chatham with boys from the Maths School in Rochester and Holcombe Tech. “I think it consisted of talking to the boys and waving to them. This of course was not done and a disgrace, so the Honour Lamp was turned off”.

In 1936, the School’s first Head Teacher, Miss Moffat, retired after having served as one year as the Principal of the ‘Trades School’ and ten as Headmistress of the Technical School. Both she and her staff had worked hard to enlarge the number of subjects taken and broaden the curriculum beyond its exclusively commercial base and the School, for example, was the first in Kent to teach French by speech alone and school visits were arranged to France.

The School now had almost 400 pupils and when Miss Moffat retired in 1936 she was replaced by Miss D.C.Collins who served as Headmistress for one term and seems distinctly Edwardian. Described as a ‘regal figure’ she had the habit of calling, ‘in ringing tones’, to passing pupils from her study window : “Keep a good posture girls” and when she attended the school sports’ day she was reported to have worn : “An attire fit for a royal garden party, complete with parasol”. She was succeeded by Miss Young whose major work was to organise the School in the first years of the Second War which broke out in 1939.

In the next chapter I shall deal with the start of the massive changes which would change the site of Fort Pitt out of all recognition in the 20th century in : Chapter Eight : The School in the Second World War and the second half of the Twentieth Century

John Cooper

.png) Given the fact that, in the 19th century Fort Pitt Military Hospital was a centre scientific research and the home of the first Army Medical School, it seems fitting that this History of Fort Pitt should end with reference to the new science block and with new sixth form accommodation opened on the site of the School in 2018. The architects, McCormack Young LLP said : ‘The challenge for HMY was to find the most suitable location creating least impact for a large building on the site. Sitting in a very prominent position above the towns of Chatham and Rochester, and with significant above and below ground heritage assets including a network of subterranean tunnels and caverns from the original military fort on the site meant that there were few suitable locations for the new science centre that would support both the working of the school and respect the heritage of the site’.

Given the fact that, in the 19th century Fort Pitt Military Hospital was a centre scientific research and the home of the first Army Medical School, it seems fitting that this History of Fort Pitt should end with reference to the new science block and with new sixth form accommodation opened on the site of the School in 2018. The architects, McCormack Young LLP said : ‘The challenge for HMY was to find the most suitable location creating least impact for a large building on the site. Sitting in a very prominent position above the towns of Chatham and Rochester, and with significant above and below ground heritage assets including a network of subterranean tunnels and caverns from the original military fort on the site meant that there were few suitable locations for the new science centre that would support both the working of the school and respect the heritage of the site’.

.png) Marked ‘9 Psychology Block’. Another late Victorian addition to the Hospital and used as a Stores and Dining Room. Below the ground, in the vicinity of ‘5 Old Science Building’ : The Fort’s underground chambers to store its ammunition, still in existence but not accessible, Grade II listed and built between 1805 and 1813.

Marked ‘9 Psychology Block’. Another late Victorian addition to the Hospital and used as a Stores and Dining Room. Below the ground, in the vicinity of ‘5 Old Science Building’ : The Fort’s underground chambers to store its ammunition, still in existence but not accessible, Grade II listed and built between 1805 and 1813..png) Marked ‘6 Music House’ and Grade II listed. The Hospital's Asylum for patients with mental illness and built in 1847. The north west boundary of the School following the line of the Fort’s north-western corner bastion.

Marked ‘6 Music House’ and Grade II listed. The Hospital's Asylum for patients with mental illness and built in 1847. The north west boundary of the School following the line of the Fort’s north-western corner bastion..png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)